Subversion of Juries in Local Government

The Grand Jury Room

Sandwich Town Hall

"A jury is a body of neighbours summoned by a public officer to answer questions upon oath."

The History of English Law Before the Time of Edward I, Frederick Pollock and Frederic Maitland (1895)

It will be seen that there is nothing in this definition which restricts the jury to judicial proceedings; on the contrary, the definition deliberately makes room for the fact that the jury, like so many institutions, was an administrative device which only late became confined to courts of law.

A Concise History of the Common Law, Theodore Plucknett (1956)

The History of English Law Before the Time of Edward I, Frederick Pollock and Frederic Maitland (1895)

It will be seen that there is nothing in this definition which restricts the jury to judicial proceedings; on the contrary, the definition deliberately makes room for the fact that the jury, like so many institutions, was an administrative device which only late became confined to courts of law.

A Concise History of the Common Law, Theodore Plucknett (1956)

Anglo Saxon Administration

Local government under the Anglo Saxons was administered through the King's Ealdorman who was responsible for a shire. The Shire-Reeve (Sheriff) was responsible for upholding law and order and holding civil and criminal courts in the shire.

Shires were divided into hundreds and tithings and members were held responsible for their members' behaviour thereby creating a very decentralised and self regulatory administrative system.

Local government under the Anglo Saxons was administered through the King's Ealdorman who was responsible for a shire. The Shire-Reeve (Sheriff) was responsible for upholding law and order and holding civil and criminal courts in the shire.

Shires were divided into hundreds and tithings and members were held responsible for their members' behaviour thereby creating a very decentralised and self regulatory administrative system.

Local Governance following the Norman Conquest

Although Anglo-Saxon society was essentially feudal in character, the Norman system was much more rigid and centralised.

Following the Conquest Anglo-Saxons were effectively dispossessed of almost all their land and ownership was centralised under the Norman monarchs.

The Norman nobility was rewarded with 'fiefs' which were parcels of land large enough to act as a unit of loyalty to the monarch but small enough to prevent the development of rival power. Each fiefdom was governed more or less independently by the Lord.

Following the Black Death feudal relationships changed to become more a relationship between lord and tenant rather than lord and vassal.

Judicial and regularity powers transferred to parishes, manors and towns.

Although Anglo-Saxon society was essentially feudal in character, the Norman system was much more rigid and centralised.

Following the Conquest Anglo-Saxons were effectively dispossessed of almost all their land and ownership was centralised under the Norman monarchs.

The Norman nobility was rewarded with 'fiefs' which were parcels of land large enough to act as a unit of loyalty to the monarch but small enough to prevent the development of rival power. Each fiefdom was governed more or less independently by the Lord.

Following the Black Death feudal relationships changed to become more a relationship between lord and tenant rather than lord and vassal.

Judicial and regularity powers transferred to parishes, manors and towns.

Manor Courts

Although historians have tended to dismiss manor courts as a relic of the Middle Ages research shows that they were essential to local governance into the 19th century and were the premier courts of the first instance in most villages and many towns.

There were two types of manorial court - the court leet and the court baron.

Although historians have tended to dismiss manor courts as a relic of the Middle Ages research shows that they were essential to local governance into the 19th century and were the premier courts of the first instance in most villages and many towns.

There were two types of manorial court - the court leet and the court baron.

Court Leet

Some manorial lords had royal authority to hold a court leet which gave the manor court jurisdiction over matters usually exercised in the hundred court.

Meeting twice a year the court leet viewed frankpledges - a freeman's oath to keep the peace and uphold good practice in trade. It sat with a jury of freeholders and tried offences such as assaults, obstruction of highways, or the breaking of the assize of bread and ale. It might also deal with the election of local officials such as constables.

In 1977 the Administration of Justice Act abolished the legal jurisdiction of court leets and they were formally abolished in 1998.

However court leets still exist throughout England and where they remain citizens can make presentments concerning local matters.

Some manorial lords had royal authority to hold a court leet which gave the manor court jurisdiction over matters usually exercised in the hundred court.

Meeting twice a year the court leet viewed frankpledges - a freeman's oath to keep the peace and uphold good practice in trade. It sat with a jury of freeholders and tried offences such as assaults, obstruction of highways, or the breaking of the assize of bread and ale. It might also deal with the election of local officials such as constables.

In 1977 the Administration of Justice Act abolished the legal jurisdiction of court leets and they were formally abolished in 1998.

However court leets still exist throughout England and where they remain citizens can make presentments concerning local matters.

Court Baron

The court baron was the principal type of court and was usually presided over by a steward or his deputy, appointed by the lord. In addition to the steward there were other officers of the court for example Constable, Hayward, Tythingman, and Aletaster.

While a steward or his deputy presided over the court, he did not judge. Decisions were made by a jury of twelve local copyholders (tenants) who had usually lived their lives in the manor and were considered to have the necessary knowledge to judge matters and to be familiar with manorial customs.

Manorial jurors met regularly to set down local rules and monitor their neighbours to ensure their implementation.

For the majority of people who rarely had any dealings with a Justice of the Peace and who never voted for a member of parliament, the semi-annual meeting of the manorial jury could be their primary encounter with the business of government.

(Governing England through the Manor Courts, 1550-1850 by Dr. Brodie Waddell )

According to Waddell a wealth of information about local government preserved in the manorial records remains largely undiscovered and overlooked by historians. For example in their nine volume history of English Local Government Sidney and Beatrice Webb dismissed the non-agricultural functions of eighteenth century manorial courts and claimed that by 1689 the institution was a ‘court in ruins’, ‘in every instance falling into decay’.

The court baron was the principal type of court and was usually presided over by a steward or his deputy, appointed by the lord. In addition to the steward there were other officers of the court for example Constable, Hayward, Tythingman, and Aletaster.

While a steward or his deputy presided over the court, he did not judge. Decisions were made by a jury of twelve local copyholders (tenants) who had usually lived their lives in the manor and were considered to have the necessary knowledge to judge matters and to be familiar with manorial customs.

Manorial jurors met regularly to set down local rules and monitor their neighbours to ensure their implementation.

For the majority of people who rarely had any dealings with a Justice of the Peace and who never voted for a member of parliament, the semi-annual meeting of the manorial jury could be their primary encounter with the business of government.

(Governing England through the Manor Courts, 1550-1850 by Dr. Brodie Waddell )

According to Waddell a wealth of information about local government preserved in the manorial records remains largely undiscovered and overlooked by historians. For example in their nine volume history of English Local Government Sidney and Beatrice Webb dismissed the non-agricultural functions of eighteenth century manorial courts and claimed that by 1689 the institution was a ‘court in ruins’, ‘in every instance falling into decay’.

Manorial Jury Presentments

Manorial juries were where the tenants made decisions across a broad range of issues. They managed common pastures and local resources including fuel, timber, fish and game.

They judged and punished those who:

Tenants regulated immigration into their local area. Current tenants were prohibited from subletting or providing lodging to the mobile poor and new dwellings could not be built unless they had four acres of land.

Local archives have presentments issued for those who:

Manorial juries were where the tenants made decisions across a broad range of issues. They managed common pastures and local resources including fuel, timber, fish and game.

They judged and punished those who:

- disrupted the peace of the neighbourhood;

- over-exploited shared resources;

- neglected to fulfil their duties as members of the community, for example attending the common days work for mending highways,

- Traders who tried to sell their wares at unlawfully high prices or charge excessive tolls were prosecuted.

Tenants regulated immigration into their local area. Current tenants were prohibited from subletting or providing lodging to the mobile poor and new dwellings could not be built unless they had four acres of land.

Local archives have presentments issued for those who:

- neglected to repair roads and paths adjoining their land,

- obstructed streets with dunghills or sandpits

- removed stiles and bridges on their footpaths

- failed to maintain enclosures and boundaries necessary to manage livestock and define holdings

- let individual homes, especially chimneys, fall into disrepair

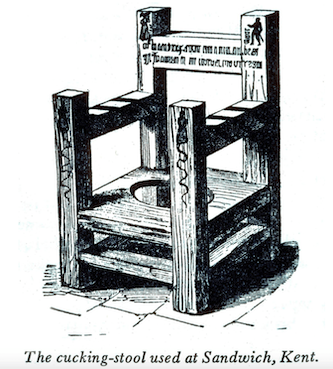

CUCKING and DUCKING STOOLS

A scold was someone who disturbed the peace, fought loudly, gossiped, slandered others, or spewed blasphemy. As punishment they were affixed to cucking stools in order to humiliate them.

Ducking stools emerged later. Rather than display a scold to neighbours or parade them through town, they affixed scolds to chairs at the end of a long pole, made of iron or wood, and dunked them in the water.

The Grand Jury Room

Maison Dieu House, Dover Town Hall

County Quarter Sessions

Alongside the Manor Courts the government of English counties was in the hands of Justices of the Peace (JPs) assembled in Quarter Sessions.

Here grand juries investigated matters that were considered blameworthy but not a violation of criminal law.

They could issue presentments and reports publicising and condemning certain practices of both private citizens and public officials. These were addressed to the supervising court and were available to the public and covered matters such as:

G.G. Alexander (1915) describes the JPs as "a class of country gentlemen who were experts in the work of county administration. On the whole the work was performed with great ability and economy. But it was thought to be out of harmony with the democratic spirit of the age that such large powers of raising money (by means of the county rate) and spending it should be in the hands of unelected and unrepresentative agents. "

Through a series of 19th century Acts of Parliament local government was transferred from long established courts and juries and placed in the hands of elected officials.

Alongside the Manor Courts the government of English counties was in the hands of Justices of the Peace (JPs) assembled in Quarter Sessions.

Here grand juries investigated matters that were considered blameworthy but not a violation of criminal law.

They could issue presentments and reports publicising and condemning certain practices of both private citizens and public officials. These were addressed to the supervising court and were available to the public and covered matters such as:

- the condition of prisons

- the upkeep of public amenities including highways, bridges, sewers and stocks

- illegal gaming and unlicensed victualling

- weights and measures

- misconduct in public office

G.G. Alexander (1915) describes the JPs as "a class of country gentlemen who were experts in the work of county administration. On the whole the work was performed with great ability and economy. But it was thought to be out of harmony with the democratic spirit of the age that such large powers of raising money (by means of the county rate) and spending it should be in the hands of unelected and unrepresentative agents. "

Through a series of 19th century Acts of Parliament local government was transferred from long established courts and juries and placed in the hands of elected officials.

Elected Councils Imposed

In 1835 the Municipal Corporations Act changed local government by introducing election of 'town' councillors by rate payers.

It was part of the reform programme of the Whigs under Lord Grey and followed recommendations from a royal commission dominated by Radicals, with Joseph Parkes Secretary.

In 1835 the Municipal Corporations Act changed local government by introducing election of 'town' councillors by rate payers.

It was part of the reform programme of the Whigs under Lord Grey and followed recommendations from a royal commission dominated by Radicals, with Joseph Parkes Secretary.

In 1888 the Local Government Act established elected county councils and county borough councils in England and Wales.

It followed the 1886 general election where a Conservative administration headed by Lord Salisbury did not win a majority of seats and had to rely on the support of the Liberal Unionist Party. To secure their support the Liberal Unionists demanded that a bill be introduced placing county government under the control of elected councils modelled on the 1835 Act.

It followed the 1886 general election where a Conservative administration headed by Lord Salisbury did not win a majority of seats and had to rely on the support of the Liberal Unionist Party. To secure their support the Liberal Unionists demanded that a bill be introduced placing county government under the control of elected councils modelled on the 1835 Act.